Despite facing persistent challenges, some Latino immigrants are relocating to the United States to work on the backside in hopes of creating a better life for their families. Making the transition isn’t easy, but their perseverance is what keeps them going.

Written By Sarah Kelley | Photos by Kylene White

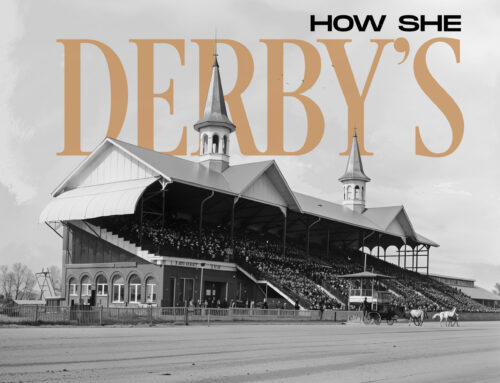

The stands at Churchill Downs are empty on this cold, crisp April morning, but the backside of the iconic racetrack is bustling. A steady stream of exercise riders atop majestic thoroughbreds enter and exit the dirt track, taking turns running horses 30 minutes at a time.

Behind the track, the clip-clop of hooves on pavement echoes between rows of white barns. Inside Barn No. 26, Bertila Quinteros is tending to a chestnut-brown filly. Seated beneath the imposing 3-year-old, she scrubs dirt off its horseshoes, lifting each leg with a confident-yet-gentle touch.

“This one is sweet and quiet in the stall, which is good,” says Bertila, who’s worked as a groom at Churchill Downs for 20 years. During her two decades on the job, she’s encountered plenty of wild horses, too — “many of them boys,” she jokes.

Bertila is one of around 1,000 backside workers during a racing season that spans early spring through late fall, punctuated by the Kentucky Derby on the first Saturday in May. The vast majority of those workers are Latino immigrants like Bertila, who grew up on a small coffee farm in Guatemala.

But as a woman on the backside, Bertila is in the minority, as less than one-third of the workforce is female. She’s part of a community of women who have overcome immense obstacles and personal struggles to build better lives for their families.

The number of women on the backside began increasing in conjunction with the influx of Latino immigrants in the 1990s and early 2000s, says Sherry Stanley, executive director of the nonprofit Backside Learning Center at Churchill Downs. Historically, women were not even allowed on the backside, a restriction that was loosened by the 1980s.

Bertila Quinteros is one of nearly 1,000 backside workers during a racing season at Churchill Downs. The majority of those workers are Latino immigrants.

In 2012, Indiana University Southeast conducted a study on the “needs and perceptions” of the backside and determined around 30% of workers were women (an estimate that has since remained steady). Researchers interviewed workers and horse trainers for the study, and they included this notable observation: “One trainer made a point of saying his female workers were by far his most responsible and efficient workers.”

Many of the women come from the same small towns in Mexico and Guatemala, where they learned of opportunities at Churchill Downs via word of mouth. The majority of Guatemalans come from the city of Santa Rosa, which has the highest level of poverty and violence in the country, according to Sherry.

Santa Rosa is the place Bertila calls home.

“When I moved here my son was just 2 years old, and I missed him a lot,” says Bertila, who left her son with family in Santa Rosa. “That was the most difficult year of my life.”

Bertila starts her day at 4:30 a.m. and cares for four or five horses.

‘Their lives are so overwhelming’

When Esperanza Espinoza immigrated to the United States, she did so for the sake of the two young children she was leaving behind in Puebla, Mexico.

“I wanted to help my kids grow up with a better future,” says Esperanza, whose husband had previously left Mexico and found work in the U.S. equine industry. Eventually, Esperanza joined him, and for the past 10 years the couple has worked at Churchill Downs — he’s a groom, she’s a hotwalker, walking horses to warm them up and cool them down.

Esperanza’s 23-year-old daughter has since immigrated and is working alongside her parents on the backside, with the hopes of continuing her education; her 17-year-old son is still in Mexico, where he’ll soon finish high school; and she now has two more children born in the U.S. “My dream is that my kids can get a degree in college and have a future.”

It’s a familiar story among women of the backside, many of whom are mothers juggling grueling work schedules, raising children and supporting families back home.

“Their lives are so overwhelming,” says Keren Jemima Davila Suarez, director of the women’s ministry at Christ Chapel on the backside. The nonprofit Kentucky Racetrack Chaplaincy operates the chapel, which offers services such as a free clothing closet and food pantry.

Many of the women working on the backside have faced intense personal struggles, according to Keren, but you wouldn’t always know it. “They say they are fine and have a strong façade,” she says.

That’s in part because the women simply don’t have the option to quit.

“It has been difficult but not impossible,” says Bertila, a single mother of not only the son she had in Guatemala, but of a daughter born in the U.S. She and the father of her children broke up soon after their second child was born.

“I knew this wasn’t the last hard thing that was going to happen, but I just had to keep going and make it work. My daughter was really small. I knew I had to send this girl to college by myself.”

Now both her kids are in college — her 23-year-old son in Guatemala, where he’s studying agriculture, and her 19-year-old daughter at the University of Louisville, where she’s studying medicine. Their dreams are coming true.

“They are both in college now and work,” says Bertila. “I am so proud of them.”

‘A very strong girl’

Back at Barn No. 26, it’s 8:30 a.m. and Bertila has been working since 4:30. After all these years, the early start time remains the hardest part of the job — especially on cold, damp days like this. As the cold weather lingers in Louisville, she longs for the warmth and lush green beauty of Guatemala, a place she hasn’t visited since departing 20 years ago. However, she gets a glimpse during daily Facetime calls with her son.

“I am very lucky because my parents can come here and visit,” Bertila says in slow, deliberate English, which she learned via classes at the Backside Learning Center. That’s also where she takes yoga — “And Zumba!” she exclaims.

Today, Bertila is charged with caring for four horses: spreading fresh hay, sponging them off, wrapping their ankles in white cloth bandages, feeding them a breakfast of mixed grains.

When asked if she has a favorite horse among the two dozen currently housed in the barn, Bertila motions a few stalls down. As we approach, the dark brown filly walks up and initiates a nuzzle.

“She’s gorgeous and sweet, but she’s tough when she runs,” Bertila says, stroking the horse’s mane. “She’s a very strong girl.”